- Heritage Stories

A short history of The Close Theatre Club

In 2015, we held our Up Close season, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the notorious but short-lived Close Theatre. We asked playwright Jenny Knotts to share some of her research on The Close Theatre.

On the evening of Tuesday 29 September 1964, throngs of cars carrying guests and supporters of the Glasgow Citizens Theatre drew up along Gorbals Street. The occasion was a Gala evening to celebrate the 21st anniversary of the company. Adorned in evening wear, a stipulation usually reserved for opening nights, audience members poured into the majestic foyer ahead of the main event – a revival of James Bridie’s ‘A Sleeping Clergyman’.

As the curtain fell, the Chairman of the Board of Directors, Michael Goldberg, took to the stage to herald the imminent opening of a new workshop theatre, adjunct to the Citz, that would devote itself to theatrical experimentation. This intimate theatre would provide artists with a space to explore new texts and techniques free from the constraints and pressures of the proscenium arch. The announcement was met with rapturous applause and extensive media coverage as plans for the latest venture of the Citizens Theatre Company, and certainly its greatest since its move to Gorbals Street from the Athenaeum in 1945, got underway.

Nearly a decade later, in May 1973, staff and helpers scrambled among the ashes of the destroyed Close Theatre Club in a bid to salvage some evidence of the near 200 productions that had taken place ‘up the close’ at 127 Gorbals Street. Nowadays there is no physical remembrance of The Close Theatre, however its legacy can be found not only in the Tron Theatre, which was eventually formed to help fill the void created by the 1973 fire, but also in the very nature of modern theatre in Scotland. Despite its untimely demise, The Close Theatre Club altered the landscape of Scottish theatre forever.

Citizens Theatre founder James Bridie.

The Close Theatre was destroyed by fire 1973.

The Close Theatre Club was born from an ongoing rumbling of unrest, both within its parent theatre, the Citz, and in the wider Scottish theatre community. The Citizens Theatre came under a great deal of pressure from patrons and the press to produce more new work. Aware of these demands and the building’s own growing pains, Goldberg kept a watchful eye on a former dance hall, now notorious pitch and toss club, which lay directly adjacent to the Citizens. In a fittingly dramatic twist of fate, a violent murder led to the immediate closure of the club. Goldberg seized the opportunity and stepped in.

The idea of a small experimental theatre was not merely enthusiastically welcomed but seemed pertinent to the company’s development. As Director of Productions, Ian Cuthbertson attested: “Every industry has its research department: the theatre is in no way different, only well behind.”

It was agreed that this would be an exciting venture giving the opportunity for trying out new actors, new plays and new playwrights, and to give full-time work to more actors.

From the outset it was decided that the Citizens and Close Theatres would complement each other wherever possible, sharing both facilities such as scenic workshops, and staff including actors and technicians. One actor, Dermot Tuohy, managed to perfectly embody this mutual benefit in the early days of The Close Theatre by playing a small role in first act of the main stage production, then dashing offstage and upstairs to play a prominent role in the second piece in that night’s Close double bill.

The Close Theatre quickly carved a niche for itself in staging lesser seen works by well-known writers as well as brand new pieces. Olwen Wymark’s first play Lunchtime Concert was a notable success in the early years of the venture and was later revived in a triple bill of the playwright’s work – testament to the theatre’s dedication to developing emerging artists.

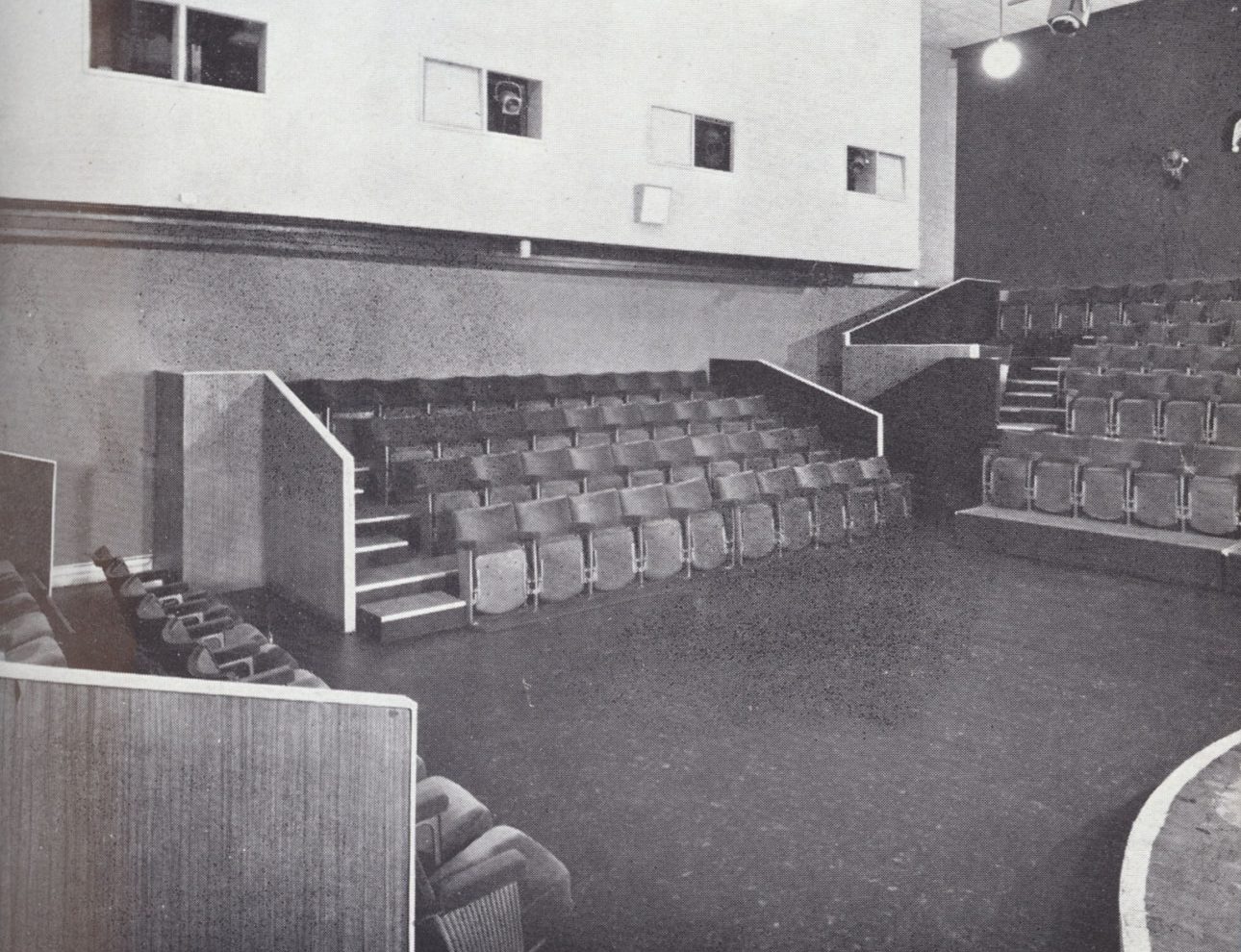

One-act plays were preferred, with audiences usually being treated to a double bill – on occasion returning after the interval to discover the layout of the theatre had changed entirely during the interval from apron to in-the-round; such was the diversity of the space. Later script readings, film nights, opera and even ballet would grace its versatile stage.

An infamous episode in 1965 involving Charles Marowitz, an interesting interpretation of Doctor Faustus and a mask of the queen’s face, resulted in the abandonment of the opening night performance in favour of an impromptu debate between audience and management about whether the show should go ahead. The incident afforded the club its first front page controversy, and sparked interest far and wide in the new little theatre. With membership soaring to over 2,000, The Close Theatre Club firmly cemented its position as the most theatrically exciting venue on the west coast.

Director Charles Marowitz”s Doctor Faustus in The Close Theatre caused controversy.

With the arrival of Giles Havergal, Philip Prowse, and later Robert David MacDonald, The Close Theatre continued to be a hive of theatrical experimentation and boundary-shattering productions. So too, however, was the main stage.

While The Close Theatre undoubtedly offered theatre goers a unique experience in the intimate nature of the auditorium and the buzzing social hub of the bar, it was no longer the only place on Gorbals Street one could find theatrically outlandish and exciting work. Of course, there were certain productions that would never have been possible, or as effective, on the Citz main stage, such as Artaud’s The Cenci which hit headlines with its naked photo call and introduced Scottish theatregoers to the concept of the Theatre of Cruelty. In the latter days, just as popular as the productions themselves were the nightclub and restaurant (doubling as staff canteen) which made it the place to be and to be seen.

Yet its original purpose was no longer quite as urgent as it had been in the early years of its life. In the years following the fire Giles told Michael Coveney:

In the old days The Close was a leech, using a lot of manpower and resources, and it drove us mad. But once we were up and running we felt differently about its loss – to the extent that, today we feel we could once again do with another space.

Of course, the Citizens would later acquire not one, but two studio spaces each of which hosted some of the company’s most exciting work.

As the trendiest place to be seen in Glasgow, the city’s first unofficial gay bar and the only place either side of the river to serve drink on a Sunday, The Close Theatre Club contributed much more to the cultural fabric of Glasgow than simply theatre. Its significance cannot be overestimated. Not only was the intimate theatre the first of its kind in Glasgow, but the Citizens Theatre was the only one in Britain to harbour two theatre spaces under one roof at the time. In this achievement alone we can regard The Close Theatre Club as a pioneering enterprise in British theatre as the studio space gradually became a staple in venues up and down the country. The Close Theatre stage was also home to a plethora of theatre heavyweights during the formative years of their careers including Steven Berkoff, David Hayman, Peter Kelly, Ann Mitchell, Ida Schuster, Billy Connolly (who would later headline a post-fire Close Theatre benefit gala) Richard Wilson and many more. The Close Theatre Club undoubtedly marked a key moment in Scottish theatre – now immeasurably richer for its existence.

You may be interested in

- Heritage Stories

Jessica Worrall on her digital collage exhibition

- Heritage Stories

Celebrating 20 years of community theatre

- Heritage Stories