- Heritage Stories

Giles Havergal: a theatre for the Citizens

Post Written by Erika Rodríguez Horrillo. MLitt Theatre Studies student, on placement in Glasgow University’s Archives and Special Collections department.

It’s 1969 in Glasgow. The city doesn’t know it yet, but it’s about to witness a real theatrical revolution: Giles Havergal arrives at the Citizens Theatre as its new Artistic Director, and the scene is set for a showdown. Over his 33 years’ tenure, Havergal will make the Citizens a theatre not just for the people of Glasgow, but one that’s a reference to the world.

Over the past few months, I’ve been going through countless boxes of material from the Giles Havergal and Citizens Theatre Collections at the Scottish Theatre Archive (STA) as part of my Theatre Archive Placement for the MLitt Theatre Studies programme. I remember the excitement of the first day I arrived in the Archive and I was given a tour and introduced to the amazing people that work there. I remember the thrill that overcame me when I saw the huge room full of shelves containing books, documents, posters, and even costumes and objects related to shows and artists. I knew the Archive was big, but that’s when I got a real notion of the magnitude of it – and it’s incredible to know that we have access to all those materials in our University Library!

When I first heard the name Giles Havergal while looking for a collection to explore in the STA, I had no idea of who he was or what he had done to have an entire collection dedicated to him. I must excuse myself here – I am Spanish and didn’t know much about Glaswegian/Scottish theatre when I first arrived. However, I had been to the Citizens Theatre on several occasions and had collaborated with them in social projects, so I couldn’t wait to learn more about the person who made that amazing theatre what it is today – and now I can share it all with you!

Hard beginnings

The Citizens Theatre opened as such in 1945, when the Citizens’ Company, directed by James Bridie, moved into the former Royal Princess’s Theatre Gorbals Street. The Gorbals is an area in the city of Glasgow on the south bank of the River Clyde, not far away from the city centre. Due to overpopulation, the area was subject to several remodelling plans in the 20th century that included the construction of multiple social housing tower blocks. Opening a theatre in this location may not have sounded like a strange idea, and indeed it has often been hard to attract local audiences.

When Havergal arrived in the late ‘60s, the Citizens had been through seven different artistic directors in nine years, the last of whom lasted less than a year. The theatre was under threat: audience numbers were very low, and there were plans of taking the theatre to a new more central location. But Havergal was determined to stay and offer the people of Glasgow an entertainment that would defy that of the Palace Bingo next door. And so he did.

The Triumvirate

The Edinburgh-born director arrived in Glasgow straight from the Palace Theatre at Watford and brought designer Philip Prowse with him. A year later, Scottish writer and translator Robert David MacDonald would join them, and together they would direct the theatre for 33 years in what has been known as the Triumvirate, or as some referred to it, the ‘Unholy Trinity’. In a short time, they would transform the theatre in all ways possible, and make it one of the leading theatres in Britain, contributing to Glasgow becoming European City of Culture in 1990.

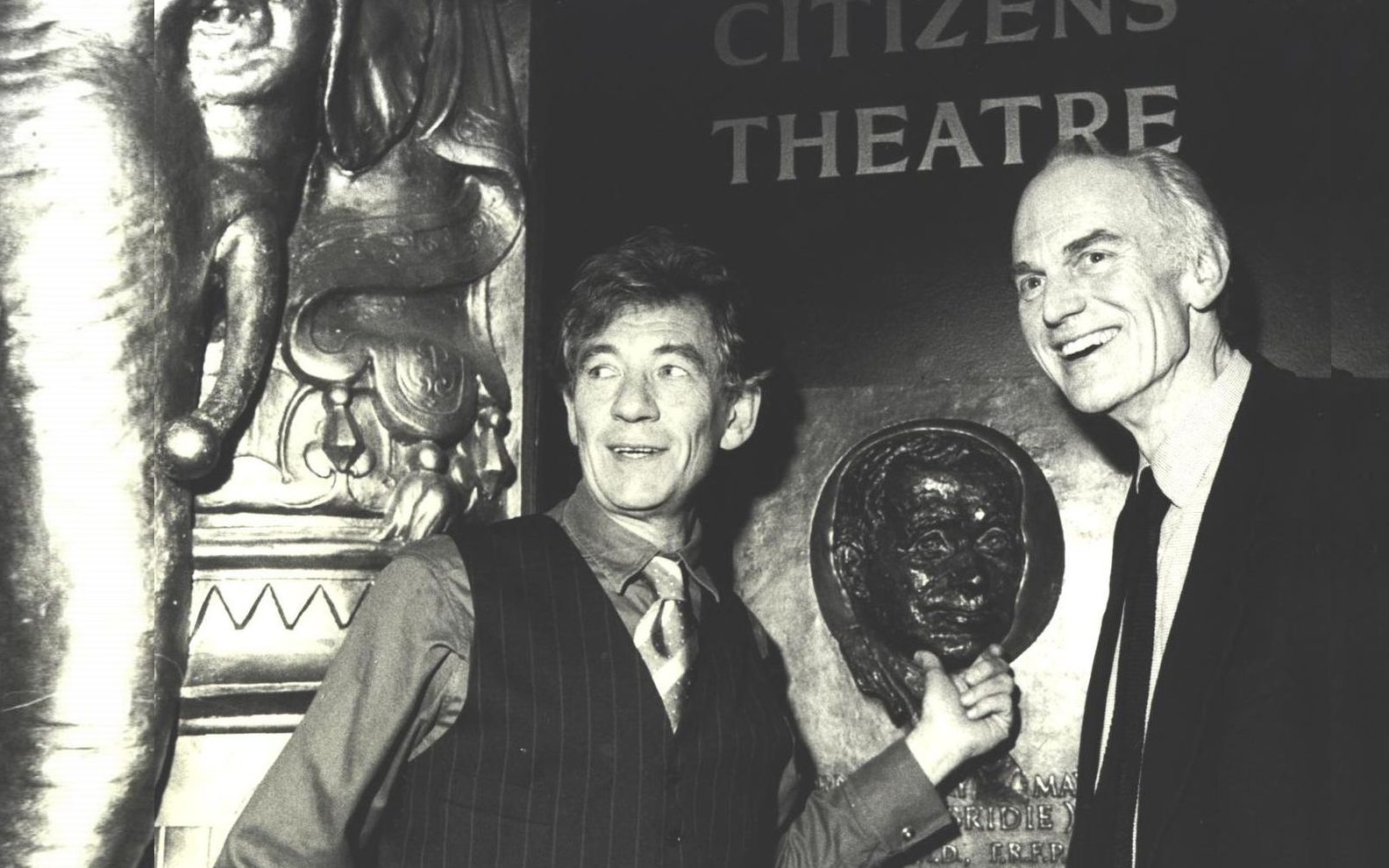

Philip Prowse, Giles Havergal and Robert David MacDonald.

Ref: STA GHC 4/49/4

Hamlet

But how did Havergal succeed in a task where so many had struggled before? We could say that everything started with a very controversial production of a Shakespeare play: on 4 September 1970, Hamlet opened at the Citizens Theatre, and as theatre critic Michael Coveney would say years later, “all hell [broke] loose”.

Prowse had the idea of gathering a bunch of young actors and creating innovative productions of classic plays. If nobody liked what they did, he said, they could do what they liked. Giles Havergal directed an all-male production of Hamlet that included representations of sex and partial nudity, which challenged 20th century morality. The production provoked an outburst of critics and the cancellation of bookings by many schools. That could had been the end of Havergal’s directorship.

However, contrary to the predictions of newspaper critics, the immediate results of the controversy were packed houses and new young audiences that came to theatre attracted by the sense of rebellion and disinhibition experienced there. It was the beginning of a 33-year reign marked by socialism, provocation, and theatrical splendour.

‘Hamlet’ may indeed be going to Hell on a bicycle.

Ref: STA GHC 2/11

The Scottish matter

To the Hamlet debate others would follow. The Triumvirate was often criticised for the lack of Scottish plays in their programme. They would very rarely put on plays by Scottish authors, to which Havergal would argue that the company had a Scottish playwright in their team, Robert David MacDonald, and that the plays they received were often not good enough. Some of the board members would disagree with this claim, to which the Triumvirate would reply that the plays might read well, but not stage well.

Keys to success

On a visit to Waverly Secondary School in Glasgow at the beginning of his tenure, Havergal told the school magazine that he thought the problem with the Citizens was that it had never been anything for long enough, and that what the theatre needed was “a consistent policy over a few years” that would help build up the audiences. He did indeed give the theatre this consistency throughout the three decades of his tenure, and his policies proved to be very successful.

Some of his ideas were absolutely revolutionary. With Prowse’s aid, Havergal would introduce multiple socialist policies to the theatre, the most acclaimed of them being the low ticket-pricing. For many years, all tickets were 50p, with senior citizens and the unemployed having free entrance to every show. The prices increased with time, but they were always kept affordable to everybody. All actors in the company would be paid approximately the same (recently graduated actors would be paid slightly less), and they would be cast in leading and small parts interchangeably, giving them a chance to play big roles that they wouldn’t probably be offered elsewhere. They also introduced the alphabetically ordered staff-list that remains to this day, which gives an egalitarian status to every member of the staff.

The triumvirate was always faithful to their own beliefs and not to what audiences/critics expected from them. This refusal to patronise the public, together with an outstanding financial management (the theatre never ran up a deficit under Havergal’s tenure), were vital to the Citizens Theatre’s success under the Triumvirate’s reign.

New look for the Citz

In 1989, just in time for the 1990 double celebrations of the 21st anniversary of the new Citizens Theatre Company and Glasgow being named European City of Culture, the theatre was given a complete makeover, giving birth to the Citizens as it is remembered by many. This design of the theatre was inspired by Glasgow’s shipbuilding past. The new foyer was covered by a glass and metallic structure, and it included new bar premises. A new studio theatre had been set up during the works so that the season could go on, and they decided to keep it going when the works were over. It wasn’t the first time The Citizens housed a studio theatre. In fact, until it burnt down in 1974, The Close Theatre cohabited with the Citizens for many years.

Whilst the main auditorium has remained the same since it’s construction in 1878, the theatre has been through renovation and expansion several times. The first big remodelling of the theatre would come in the ‘70s, when the neoclassical façade of the old Royal Princess’s Theatre (previously known as Her Majesty’s Theatre), comprising six columns topped by the four muses of theatre flanked by the two bards, Shakespeare and Burns, was demolished. The goddesses were kept safe until they were restored to the new foyer in 1989, and all the statues were returned to the roof of the new Citizens Theatre building in 2023, as part of the theatre’s latest redevelopment.

Death in Venice. Citizens’Theatre, Glasgow.

Photographer Alan Wylie. Ref: STA GHC 8/38

Death in Venice. Citizens Theatre, Glasgow.

Photographer Alan Wylie Ref: STA GHC 8/38

Giles Havergal’s Legacy gave up his directorship of the theatre in 2003, but he kept working as an actor with his one-man production of Death in Venice. This was highly acclaimed and was programmed overseas in San Francisco and New York.

Havergal lives in London. In 2017, he attended the rehearsals of a revival of his adaptation of Graham Greene’s Travels With my Aunt at the Citizens. The theatre keeps being the welcoming, socially conscious place he conceived alongside Prowse and MacDonald. He created a temple of creativity where some of the most acclaimed actors in the UK, such as David Hayman, Pierce Brosnan, or Alan Rickman, took their first steps in theatre.

Havergal didn’t give the audience of Glasgow what they wanted, or rather, what they expected. But he did make theatre for the citizens of Glasgow. His European-based repertoire was affordable to all social classes, and he brought to them plays that couldn’t be seen anywhere else in Scotland. Glasgow theatrical landscape wouldn’t be the same without the Citizens Theatre, and the Citizens would not be what it is today if it wasn’t for Giles Havergal.

If you want to learn more about him and his legacy, I genuinely encourage you to visit the Special Collections Department at Glasgow University Library, and have a look at the STA GHC collection that Giles Havergal himself has donated to the Scottish Theatre Archive. For more information about the topic, you can also turn to the Citizens Theatre Collection (STA CTC).

You may be interested in

- Heritage Stories

Jessica Worrall on her digital collage exhibition

- Heritage Stories

Celebrating 20 years of community theatre

- Heritage Stories